NYU Bridge to Tandon - Week 1

July 06, 2020

Discrete Math Section 1.1

Logic is the study of formal reasonabing. A proposition is the base element. A proposition is a declarative sentence that is either true or false. eg The sky is blue, the house is warm, there are infinite prime numbers. It cannot be a command, eg close the door, say goodbye. It cannot be a question, eg have you had breakfast?

A proposition has a truth value.

| Proposition | Truth Value |

|---|---|

| The sky is blue | True |

| 2 + 2 = 5 | False |

We can assign propositions to propositional variables.

p: January has 31 days

q: February has 33 days

A compound proposition connects propositions with logical operators.

Conjunction (the and operation) is signified with ^ - for example p is true, q is false, p ^ q is false. A conjunction is true if and only if all elements are true. In other words, false ^ false = false.

| p | q | p ^ q |

|---|---|---|

| T | T | T |

| T | F | F |

| F | T | F |

| F | F | F |

Disjunction (the or operation) is denoted by v - that is, p v q = true because p is true. A disjunction is true if ANY of the propositions are true. That is, a disjunction is false only if both propositions are false. Disjunction is technically the “inclusive or”

| p | q | p v q |

|---|---|---|

| T | T | T |

| T | F | T |

| F | T | T |

| F | F | F |

There is also the exclusive or (XOR) denoted by ⊕. p ⊕ q is true if ONLY one of the two propositions are true. That is, both cannot be true at the same time (eg I am married ⊕ I am single, I am at the movies ⊕ I am in bed at home)

| p | q | p ⊕ q |

|---|---|---|

| T | T | F |

| T | F | T |

| F | T | T |

| F | F | F |

Negation (the not operation) takes a boolean and returns the opposite. Denoted by ¬

| p | ¬q |

|---|---|

| T | F |

| F | T |

Discrete Math Section 1.2

Compound propositions can be made up of more than one operation. eg p ^ ¬q

There is a precedence list that determines order of operations if no parentheses are applies. In priority:

- ¬ (not)

- ^ (and)

- v (or)

Examples:

- p ^ q v r => (p ^ q) v r

- p v q ^ ¬r => p v (q ^ (¬r))

The reduction of p ^ ¬(q v r) when p is T, q is F, r is T is in steps

- p ^ ¬(q v r)

- T ^ ¬(F v T)

- T ^ ¬(T)

- T ^ F

- F

Truth tables will have 2^n number of rows where n is the number of unique variables. eg for p, q, r there are 8 rows total for every unique combination. One strategy when filling out truth tables is intermediate columns. eg if you have p, q, r and solving for ¬q ^ (p v r)

| q | p | v | ¬q ^ (p v r) |

|---|

Then start by adding columns in the middle

| q | p | v | ¬q | (p v r) | ¬q ^ (p v r) |

|---|

Exercise 1.2.4a

| p | q | ¬p ⊕ q |

|---|---|---|

| T | T | T |

| T | F | F |

| F | T | F |

| T | T | T |

Exercise 1.2.4d

| p | q | r | r v p | (¬r ∨ ¬q) | (r ∨ p) ∧ (¬r ∨ ¬q) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T | T | T | T | F | F |

| T | T | F | T | T | T |

| T | F | T | T | T | T |

| T | F | F | T | T | T |

| F | T | T | T | F | F |

| F | T | F | F | T | F |

| F | F | T | T | T | T |

| F | F | F | F | T | F |

Discrete Math Section 1.3

Conditional operation is denoted by —> and expressed as p —> q “if p then q”. If P is true and Q is false, then p —> q is false. Else, p —> q is true. eg if there is a traffic jam then I will be late to work. if P (there is a traffic jam) and q (I am not late to work) then p —> q is false, because my predicate did not yield my expectation. if P is false (no traffic jam) and Q (i am late to work), p—> q still holds. In a conditional, we call p the hypothesis and q the conclusion. If the hypothesis is false, the conditional is true. Truth Table below.

| p | q | p —> q |

|---|---|---|

| T | T | T |

| T | F | F |

| F | T | T |

| F | F | T |

Think of it as a contract. The only way for the contract to be broken is if predicate P is true and consequence Q doesn’t happen. eg if I sleep 8 hours I will feel rested. That contract can only be proven false if I sleep 8 hours and wake up feeling tired.

Terms to know:

The converse of p —> q is q —> p (converse means flip arguments). The contrapositive of p —> q is ¬q —> ¬p (contrapositive means negate and flip). The inverse of p —> q is ¬p —> ¬q (inverse means negate).

From book:

| Proposition: | p → q | Ex: If it is raining today, the game will be cancelled. |

|---|---|---|

| Converse: | q → p | If the game is cancelled, it is raining today. |

| Contrapositive: | ¬q → ¬p | If the game is not cancelled, then it is not raining today. |

| Inverse: | ¬p → ¬q | If it is not raining today, the game will not be cancelled. |

The biconditional operation is expressed by p <—> q and means “p if and only if q”. That is, if p == q then p <—> q is true, else false. In other words, p <—> q means p == q.

For compound propositions, —> and <—> take lower precedence than negation, conjuction, or disjunction when no parentheses are applied. This means that the proposition p --> q ^ r is the same as p --> (q ^ r).

Discrete Math Section 1.4

A tautology is a compound proposition that always evaluates to true. That is, for all inputs, the result is true. Consider p ∨ ¬p

| p | ¬p | p ∨ ¬p |

|---|---|---|

| T | F | T |

| F | T | T |

A contradiction is a compound proposition that always evaluates to false. That is, for all inputs, the result is false. Consider p ^ ¬p

| p | ¬p | p ^ ¬p |

|---|---|---|

| T | F | F |

| F | T | F |

To prove something is not a tautology, you need to find the set of inputs that returns false (that is, anything false means the entirety cannot be a tautology). To prove something is not a contradiction, you need to find the set of inputs that returns true (that is, anything true means the entirety cannot be a contradiction).

Logical equivalence - two compound propositions are said to be logically equivalent if they have the same truth value for all individual proposition values. We denote logical equivalence with =, for example for p and ¬¬p, for all values of p, p = ¬¬p. Propositions s and r are logically equivalent if and only if s <—> r is a tautology (that is, for all s and r, s == r). We can compare with a truth table.

| p | ¬p | p -> ¬p |

|---|---|---|

| T | F | F |

| F | T | T |

De Morgan’s Laws are logical equivalences to show how to distribute negation inside a parenthesized expression.

The first law is

¬(p ∨ q) ≡ (¬p ∧ ¬q)

That is, you can distribute the negation to the inner elements of a paren and convert disjunction to conjunction. In code !(true || true) == !true && !true. Imagine in English.

p: “I am hungry” q: “I have a headache”.

De Morgan’s law says that “It is not true that I am hungry or I have a headache” is the same as “it is true that I am not hungry and I do not have a headache”. More explicitly, if it’s not true that EITHER are true, it must be true that BOTH are false.

The second law is (the same as the first, but swapping conjunction and disjunction)

¬(p ∧ q) ≡ (¬p ∨ ¬q)

Imagine in English with the same p and q as above. De Morgan’s second law states that “It is not true that I am hungry and I have a headache” is the same as ” I am not hungry or I do not have a headache”. More explicitly, if it’s not true that BOTH are true, it must be true that at least one is false.

Discrete Math Section 1.5

If two propositions are logically equivalent, then one can be substituted for another within a more complex proposition. The compound proposition before the substitution is logically equivalent to the compound proposition after the substitution. For example

p → q ≡ ¬p ∨ q

therefore

(p ∨ r) ∧ (¬p ∨ q) ≡ (p ∨ r) ∧ (p → q)

This is the substitution principle that we know from basic algebra.

There are a set of laws of propositional logic to show equivalence. Copied from text:

| Law Name | Law 1 | Law 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Idempotent laws: | p ∨ p ≡ p | p ∧ p ≡ p |

| Associative laws: | ( p ∨ q ) ∨ r ≡ p ∨ ( q ∨ r ) | ( p ∧ q ) ∧ r ≡ p ∧ ( q ∧ r ) |

| Commutative laws: | p ∨ q ≡ q ∨ p | p ∧ q ≡ q ∧ p |

| Distributive laws: | p ∨ ( q ∧ r ) ≡ ( p ∨ q ) ∧ ( p ∨ r ) | p ∧ ( q ∨ r ) ≡ ( p ∧ q ) ∨ ( p ∧ r ) |

| Identity laws: | p ∨ F ≡ p | p ∧ T ≡ p |

| Domination laws: | p ∧ F ≡ F | p ∨ T ≡ T |

| Double negation law: | ¬¬p ≡ p | |

| Complement laws: | p ∧ ¬p ≡ F and ¬T ≡ F | p ∨ ¬p ≡ T and ¬F ≡ T |

| De Morgan’s laws: | ¬( p ∨ q ) ≡ ¬p ∧ ¬q | ¬( p ∧ q ) ≡ ¬p ∨ ¬q |

| Absorption laws: | p ∨ (p ∧ q) ≡ p | p ∧ (p ∨ q) ≡ p |

| Conditional identities: | p → q ≡ ¬p ∨ q | p ↔ q ≡ ( p → q ) ∧ ( q → p ) |

Discrete Math Section 1.6

Many math statements contain variables. “x is an odd number” cannot be a proposition because the truth value depends on the value of X. However, “5 is an odd number” IS a proposition. The truth value of a statement can be expressed a function P over a variable X. A predicate is a logical statement where the truth value is a function of one or more variables. If P is “x is an odd number”, then P(5) is a proposition.

Predicates can have more than one variable, such as R(x, y, z) : x + y = z. The proposition R(2, 4, 6) is true.

The domain of a variable is the set of all possible values for the variable. The natural domain of the predicate “x is an odd number” is the set of all integers. Domains, if not clear from context, should be provided.

A non-math predicate could be “the dog ate dinner” - this depends on the dog, so P(dog). “The city has over 100,000 people” - this depends on the city, P(city).

It’s possible that for all values of the domain, a statement is true. However, if the statement contains a variable, it is a predicate and not a proposition. That is - “the dog is cute” is a predicate, where the variable is the dog, but it’s true for all values of the dog. Or if P(x) is x + 1 > 1 for all values in the domain of positive integers. For any valid x it’s true, but the statement contains a variable X and is thus a predicate.

It is possible that, for all values of a domain, a predicate is true. So if you specify every value in your predicate, you can come up with a set of propositions with defined truth values. Another way to turn predicates into propositions is with a quantifier. The logical statement ∀x P(x) means “for all values of x, P(x)“. The symbol is called the universal quantifier and ∀x P(x) is called a universally quantified statement. This means that ∀x P(x) is a proposition because it is either true or false. For example, “for all values of x in the domain of positive integers, x+1 > 1” can be defined as ∀x(x + 1 > 1).

This can be intuited as for the finite set {a1, a2, a3,… ax} then ∀x = P(a1) ^ P(a2) ^ P(a3) … ^P(ax)

Some universally qualified statements can be proven to be true by showing the predicate holds for some arbitrary value in the domain. An arbitrary value assumes nothing other than it belongs in the domain. That is, ∀x(x + 1 > 1) over the set of positive integers holds true and can be proved by selected any value.

A counterexample for a universally quantified statement is an element in the domain for which the predicate is false. If P(x) is “the fast food chain makes great burgers” and the domain is the set of fast food chains, Burger King as a value for X makes the predicate false. A more math-y example, ∀x(x^2 > x) over the domain of positive integers is proven false where x = 1.

The logical statement ∃x P(x) is read as “there exists an x such that P(x)“. ∃x P(x) asserts that at least ONE value of X in the domain makes the predicate true. ∃ is called the existential quantifier and ∃x P(x) is called an existentially qualified statement.

This can be intuited as for the finite set {a1, a2, a3,… ax} then ∃x = P(a1) v P(a2) v P(a3) … v P(ax).

An example in human words, ∃x (the fast-food chain x makes good burgers) is true for Five Guys. In math-y ideas, ∃x( x + 1 > 1) for the domain of positive integers is true for at least one value, like 1.

Some existentially quantified statements can be proven false with an arbitrary value. ∃x( x + 1 < x) for the domain of positive integers is false and can be proven with x = 1. Or subtract x from both sides, you get 1 < 0 which is false.

Discrete Math Section 1.7

It is possible to construct existential or universal quantifiers from logical operations (negation, conjunction, disjunction). Imagine P(x) : x is prime and O(x) : x is odd.

There exists some x that satisfies P(x) ^ O(x). This means ∃x(P(x) ^ O(x)) and can be proven true for x = 7. Or consider the statement “for all X, if x is prime then x is odd”. This can be stated as ∀x(P(x) -> O(x)) and can be proven false with the counterexample x = 2 (x is prime, x is not odd). The universal and existential quantifiers have higher precedence than logical operations. That means that

∀x P(x) ∧ Q(x) is the same as

(∀x P(x)) ^ Q(x)

and NOT

∀x(P(x) ∧ Q(x))

A variable x in the predicate P(x) is referred to as a free variable because it’s free to take on any value in the domain (not the same as a free variable in lambda calculus). The variable x in the quantified statement ∀x(P(x) is called a bound variable because it’s bound to a quantifier. If a statement has no free variables, it is a proposition because we can determine its truth value.

In the statement (∀x P(x)) ∧ Q(x), the variable x in P(x) is bound by the universal quantifier, but the variable x in Q(x) is not bound by the universal quantifier. Therefore the statement (∀x P(x)) ∧ Q(x) is not a proposition. However, in the statement ∀x(P(x) ∧ Q(x)), the statement binds both uses of x so this is a proposition.

We can also have logical equivalence with quantified statements. For example, the statement “Every new employee hit their deadline” can be expressed as ∀x(N(x) -> D(x)) or “for all X, if employee X is new, then employee X hit the deadline”.

Exercise 1.7.3d

∃x(T(x) ^ ¬B(x))

Exercise 1.7.3e

∀x (T(x) —> B(x))

Exercise 1.7.4c

∀x (S(x) —> ¬W(x))

Exercise 1.7.4h

∀x (¬W(x) —> S(x) v V(x))

Discrete Math Section 1.8

De Morgan’s laws can be applied on quantified statements. If you take the English sentence “not every bird can fly”, the logical equivalent is “there is a bird that cannot fly.” That is, ¬∀x F(x) == ∃x ¬F(x)

Similarly, the English sentence “it is not true that there is a child in class that is absent today” is the same as “every child is not absent”. For the predicate A(x), we can say ¬∃x F(x) == ∀x ¬F(x)

| Original | Equivalent |

|---|---|

| ¬∀x F(x) | ∃x ¬F(x) |

| ¬∃x F(x) | ∀x ¬F(x) |

Discrete Math Section 1.9

If a predicate has more than one variable, ex P(x,y), then each variable must be bound by a separate quantifier (even if the same quantifier). A logical expression with multiple quantifiers than bnid different variables in the same predicate is said to have nested quantifiers.

| Statement | Explanation |

|---|---|

| ∀x∃yP(x,y) | x and y are both bound |

| ∀xP(x,y) | x is bound, y is free |

| ∃y∃zT(x,y,z) | y and z are bound, x is free |

Consider predicate “M(x, y) : x sent an email to y” and proposition: ∀x ∀y M(x, y) which can be expressed as “Everyone sent an email to everyone” or, for every x, they sent an email to every y.

∀x ∀y M(x, y) is true if and only if for every pair x and y, M(x,y) is true. This includes x=y (sending email to self). If ANY pair of (x,y) yields false, the proposition is false.

Consider the proposition ∃x ∃y M(x, y), which is English can be stated as “there exists someone that sent an email to someone.” This is true if, for ANY pair (x,y), M(x,y) is true. False if none.

We can alternate types of nested quantifiers, and include both, for example ∃x ∀y M(x, y) which we can say in English “there is someone to sent an email to everyone”. If we switched quantifiers to ∀x ∃y M(x, y) we would say “Every person sent an email to someone.” Quantifiers are applied left to right. Think about a two player game, one player is existential player and the other universal player. Existential player tries to make expression true since you only need one true for proof. Universal player tries to make expression false since you only need one false for proof.

In this case, pretend leftmost player can select a value and tries to win. Player to the right tries to win, that is, for their win condition select the value that achieves their goal.

Imagine the domain of all integers and ∀x ∃y (x + y = 0). No matter what x picks, y wants to win by proving at least one true. So if X picks 3, y picks -3 and wins the game, yielding true.

Now imagine the opposite ∃x ∀y (x + y = 0). Now Y wants to win by getting to false. So, as soon as X picks a number Y picks anything that invalidates. If X picks 3, Y can pick 0, 3 + 0 != 0, Y wins the game and invalidates returning false.

De Morgan’s law applies to statements with nested quantifiers by toggling quantifier type when moving from outside to inside.

| Before | After |

|---|---|

| ¬∀x ∀y P(x, y) | ∃x ∃y ¬P(x, y) |

| ¬∀x ∃y P(x, y) | ∃x ∀y ¬P(x, y) |

| ¬∃x ∀y P(x, y) | ∀x ∃y ¬P(x, y) |

| ¬∃x ∃y P(x, y) | ∀x ∀y ¬P(x, y) |

Discrete Math Section 1.10

We need to sometimes express “everyone else”, that is “everyone sent an email to everyone” means I even emailed myself but “everyone sent an email to everyone else” is correct. There is the conditional operator and inequality operator that we can use, which is expressed as ∀x ∀y((x =/= y) —> M(x, y)) or, “for every person, they sent an email to everyone but themselves.”

To express uniqueness, we can use an existential quantifier (which is true for at least one) and then use inequality to reflect all others. That is, saying “exactly one person was late to work” is the same as saying “there is an X that is late to work, and everyone else is not late to work.” For the predicate L(x), this can be stated as ∃x(L(x) ^ ∀y((y =/=x) —> ¬L(y)))

We are allowed to move quantifiers to the left IF the variable isn’t involved in the left predicate. That is, for M(x, y) is “x is married to y” and A(x) is “x is an adult”, we can say “Every adult is married to someone at the party” or “for every person x, if x is an adult then there is a person y that x is married to”.

This can be written as ∀x(A(x) —> ∃y M(x, y))

We can move the inner ∃y out to the left as ∀x∃y(A(x) —> M(x, y))

Fundamentals of System Hardware

Module covers definition of a computer, types of computer, macro view of what’s inside, what components do, commonalities, communication between components, how CPU works, memory hierarchy, hard disks, networking

What is a computer? Basic definition: an electromechanical device that takes input, does processing, returns output. Types of computers? There used to be mainframes, a central point of computing for a location (eg one mainframe per university campus). Today we have servers, something in a room or data center well controlled and chilled. Lots of computational hardware (RAM, CPU). We also have desktops, laptops, tablets, even smartphones.

Components - What’s inside?

What’s inside a computer? Power supplies, motherboards (most main components attach), CPUs, memory, secondary storage (eg SSD, HDD), tertiary storage (eg CD ROM), video controller cards. All of these components communicate via the motherboard / main board along the system bus. PSUs provide conversion from line voltage to 12V or 5V for parts internally. Motherboard is referred to as “circulatory system” metaphorically due to system bus and peripheral buses. CPU is the brain - all calculations done here. Registers, CU and ALU, L1 and L2 cache, etc. Main memory is our RAM, where code and data are stored - wiped when computer shuts down. Video card / GPU - does complex calculations in parallel programmming, stores info to display on screen.

What’s common? All computers have at least one CPU, main memory (temp storage), secondary (permanent) storage. Most computers have a GPU for image rendering, a network interface (for net communication), peripheral interface (USB, Thunderbolt, etc). Each part typically does one or two of input, processing, output. eg SSD is IO, so input and output. CPU is processing.

Communication via parts or internal to machine is done via a bus. It’s a physical, bidirectional pathway between two or more devices. The system bus is the main pathway between CPU and main memory, but also carries data to/from IO devices. eg moving code from RAM to CPU for computation, then back to RAM happens via the bus.

Components -CPU

CPU is a single piece of silicon in the form of a chip, and is the only location where code can be executed. CPU runs on machine language, and operates in a fetch-decode-execute cycle. Each type of CPU has its own instruction set (x64 vs RISC-V). Each CPU has a small amount of local memory, called registers, used to perform operations and store information and results. A CPU may also have cache (L1, L2), to improve fetch time (faster than main memory).

CPU instructions are very granular and a small set, eg Move, Add, Subtract, Compare, Jump, etc etc. Mostly basic math operations. The CPU designer adds the capability to perform operations (end user programmer cannot change the instruction set). Instead, we use higher level languages that convert into instructions.

Instructions map to OpCodes (operation codes) mapped as numeric values. Instruction set is typically small (less than 100). When CPU receives an instruction, it knows what to do. eg ADD might be 0x00, AND = 0x20, JMP = 0xE9, etc etc.

Fetch-Execute (also known as Fetch-Decode): CPU finds an instruction, moves from main memory into CPU instruction register. Then CPU decodes instruction into actual logic (eg 0x00 means ADD), then potentially gets more variables from main memory (eg need to know what numbers to add). Then CPU executes (actually performs instruction on data). Then stores result somewhere. This cycle repeats and takes as little as 10 nanoseconds, meaning millions of instructions per second.

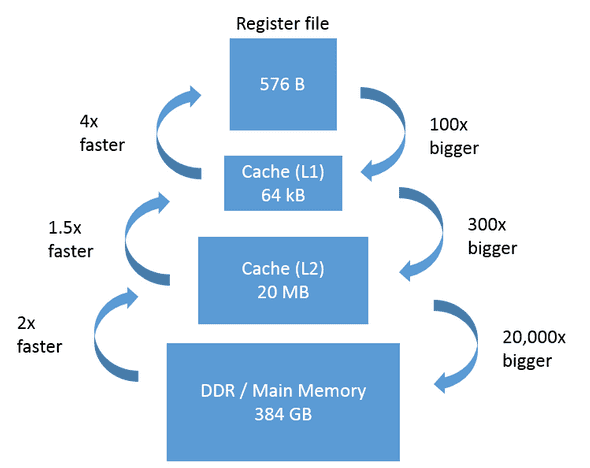

The instructions need to come from somewhere, and the CPU needs to store code in registers to execute. Why can’t we only use registers then? Expensive - registers can only hold bytes of memory, and costs a lot of money to add. Instead we have a memory hierarchy, where each layer is more space, cheaper, but slower (eg registers > cache > RAM > SSD > HDD)

Sourced from https://software.intel.com/sites/default/files/managed/5f/b0/KitchenMemoryFigureScale.png

In terms of scale, registers have nanosecond access time but can only fit bytes of data, needed for CPU instruction execution. L1 and L2 cache has nanosecond access time, measured in MB, CPU takes advantage of this automatically. RAM has ~10+ nanosecond access time, but GB of memory, volatile and cleared when system shuts down. Secondary storage has ~10 millisecond access (1 million times slower than RAM) but in terabytes, and permanent.

Components - Memory

RAM is Random Access Memory, known because its constant time to access any location (byte) in memory. Can be accessed by byte, or in units like word, int (4 bytes), etc. Volatile, so temporary and cleared when power is shut down. When a program is run, all machine language instructions are brought into RAM and pulled one by one into CPU for fetch-decode-execute.

Secondary storage can be broken down into two types.

- hard disk drives (spinning disks, measured in RPM). There’s a head that determines height and a radius (from center to edge). Different read heads for different radii. Multiple spinning magnetic discs rotate together. Moving head takes time, so moving from inner most radius, reading, then outermost radius is SLOWER than just moving to adjacent radius. Each radius is called a track and holds some data and tracks are adjacent. Moving from track to adjacent track is RELATIVELY fast, compared to big jumps. Can take in order of milliseconds for big jumps.

- Solid state drives have no moving parts. Just hold a number of chips like a USB flash drive does. All data stored in chips for the purpose of persistent storage. Data can accessed in random time (aka constant time no matter where byte is). Cost and design makes them smaller (by space) and more expensive than HDDs. Lack of moving parts also means less energy consumption.

Networking

Networking - data can come from anywhere in the world now via networks that are connected. Networks are interconnected via the internet, so effectively all devices are connected.

Computers can be connected physically via wiring. Copper is standard for ethernet, usually 8 wires in 4 pairs, in an Unshielded Twisted Pair. Fiber is newer, transmit information via light over a piece of glass (a glass cable) with less attenuation. Faster, goes further, more expensive. We also have wireless connections, usually in form of WiFi but there’s also microwave, etc.

We use protocols to determine, for example, when to start sending data, from whom, to whom - a shared language between computers for data transfer. Ethernet is both a protocol and a type of connection. Wifi is defined by 802.11. We also have ATM (asynchronous transfer mode) used for high capacity links.

We don’t really wire devices any more, like old telephones. Rather we send packets of data (~1000 bytes) using multiple protocols. Protocols can be specific to types of applications, types of logical networks, types of physical networks. Packets encapsulate information of type of protocol as a header as well as data itself, and a network layer might add some more information into header. This allows receiver to read header and determine, for example, which application is the recipient. For example, if you have two browsers open, the network response should make it obvious which broweser gets the new data.

Common layers include Application (HTTP, SMTP - simple mail transfer protocol, IMAP - internet mail access protocol). Logical aka Network, usually two layers

- connection oriented vs connectionless - ordering and guarantee of delivery like UDP vs TCP

- global delivery of packets - Internet Protocol aka IP, adds header so info can be routed back to your machine

Another layer is physical - adds header AND footer, usually for local addressing. Think Ethernet or 802.11 needs to know which device on network.

So we add, eg, an HTTP header, a TCP header, AND an 802.11 Header just to get my phone to request a website.

Positional Number Systems

Data in memory can be represented as 0s and 1s, only two states. What kinds of data can we represent? Numbers - binary representation. Text, images, video, audio, all needs to eventually be 0s and 1s. Text can be mapped as a code to a char, eg 32 -> space, 77 -> M, 126 -> ~. Images can be saved as sequence of colors (pixels), where each color is its own number value (like RGB from 0 to 255 for each of red, green, blue). Video then can be sequence of images. Audio - if we sample the voltage very frequently, we can encode audio.

We’re familiar with decimal, or base 10. Once we hit 10, we can call this “one group of ten and 0 groups of ones” - same intuition in other bases. Imagine base 5? 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 20, etc etc. Other systems are Octal (base 8), binary (base 2), hexadecimal (base 16)/

Binary - 0, 1, 10, 11, 100 (100 = 1 group of 4, 0 groups of 2s, 0 groups of 1).

Hexadecimal - 0, 1, 2…9, a, b, c, d, e, f, 10…1f, 20, 21…2f, 30

We need an idea of equivalent representations. We use subscripts, such as (13) 10 -> 13 in decimal. What is 13 in decimal to octal? (15) 8. What is 13 in base 5? (23) 5. Binary? (1101) 2. Hexadecimal? (D) 16.

Conversions

Let’s learn how to handle base conversions.

- Look at (375) 10,. We say that we have 3 hundreds, 7 tens, 5 ones. Also same as 3 * 10^2 + 7 * 10 ^ 1 + 5 * 10 ^ 0.

- What about (125) 8? 1 * 8 ^ 2 + 2 * 8 ^ 1 + 5 * 8 ^ 0.

- What about 1011 in binary? 1 * 2 ^ 3 + 0 * 2 ^ 2 + 1 * 10 ^ 1 + 1 * 10 ^ 0.

- 3b2 in hexadecimal? 3 * 16 ^ 2 + 11 * 16 * 1 + 2 * 16 ^ 0

What about decimal to base B? Let’s take 75 in decimal to binary. Well, we can come up with positional mapping. 2 ^ 8 is 256, so that position must be zero. So take the 6 digit ( 2 ^ 6 = 64) and calculate leftover, 75 - 64 = 11. Take 3 place, 2 ^ 3 =8, 11 - 8 = 3. Take 1 place, minus 2. Take 0 place, 1 - 1 = 0

75 = 00100000 + 00001000 + 00000010 + 00000001 = 001001011

Note - 1 + 2 + 4 + 8 + …2 ^ k = 2 ^ (k+1) - 1

Let’s try hexadecimal to binary. 3b9 == ? Need to map hex digit to 4 bit binary, eg 0 == 0000, 9 == 1001, a == 1010, f == 1111. So we go digit by digit. 9 -> 1001, b -> 1011, 3 -> 0011. Add them in order and you get 0011 1011 1001.

To do it backwards, we do the same. Split binary into groups of 4 (start from right to left), left pad zeros then convert via mapping. 011011010011 becomes 0011 * 2 ^ 0 + 1101 * 2 ^ 4 + 0110 * 2 ^ 8. However, that’s just the same as 6d3.

Addition

We know addition in decimals. Ones place, carry, tens digit, carry, etc etc. We can do same for anything else. Try octal: 365 + 243 -> 5 +3 = 8, so 0 and carry one. 1 + 4 + 6 = 11, or 3 and carry one. 3 + 2 + 1 = 6. 600 + 40 + 0 = 630

Subtraction

We know decimals - start with ones, then tens, borrowing from place to the left as needed. Try again in octal. 536 - 351 -> 6 - 1 = 5, then 3 - 5 doesnt work so borrow, borrow 8 from the left, 8 + 3 - 5 = 6, then 5 - 1 - 3 = 1, 165.

Signed Numbers

How do we represent -26 in binary? We don’t have negative sign, only 0s and 1s. We can use sign and magnitude or hold a bit for sign, and the rest of the bits are the magnitude, or the number value. 1 in the sign bit is negative. This is why signed integers go up to 2 ^ 31 in 32 bit architecture. We more commonly use two’s complement in computing. In a k-bit two’s complement representation:

- a positive integer is represented by its k-1 bit unsigned, padded with a zero to the left (k = 3, 01 == 1)

- The sum of a number and it’s additive inverse is 2 ^ k

Example: 26 in decimal in two’s complement using 8 bits. 26 must be represented in binary in 7 bits, or 001101 and padded bit is 0. How about -26? Well, we know how to represent 2 ^ 8 in binary (10000000), so -26 must be the value that, when added to 26 in binary, is 2 ^ 8. So 10000000 - 00011010.

Example: 00101101 as an 8 bit two’s complement. What is the decimal? Starts with a zero, so must be positive. Next 7 bits are it’s value. 45. How about 11101010? starts with a 1, so negative value. Then the sum of number and additive inverse = 2 ^ 8. x + 11101010 = 100000000, what is x? 00010110.

From Cornell - to find the two’s complement negative notation of a number: convert to binary, invert digits, add 1. So -26? First, 26 as binary in 8 bits is 00011010. Then inverted = 11100101. Then add one = 11100110. This also works converting from two’s complement. Leftmost digit, if 1, means number is negative. So let’s take 11100110 (-26) again. We know it’s a negative number because first bit, so we invert, then add one. 11100110 inverted = 00011001 then add one = 00011010, or 26!

I work and live in Brooklyn, NY building software.